Researchers at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) have pinpointed a cellular target that could enhance the way osteoporosis and other metabolic bone diseases are diagnosed and treated. The findings, published recently in JCI Insight, reveal that circulating osteoclast precursor cells (cOCPs) play a pivotal role in bone loss. The study is also the first of its kind to establish a connection between cellular biomarkers and osteoporosis, offering a potential pathway for earlier detection and more effective therapies.

“This is a new approach to understanding how we might maintain bone strength by affecting the committed precursor cells that are responsible for a lot of the damage and destruction that happens in bone, either in joints or generally in osteoporosis,” said Richard Bockman, MD, PhD, endocrinologist at HSS and co-author of the study. “This study also revealed a new target for managing bone health in metabolic bone and many orthopedic disorders.”

Osteoporosis, which affects approximately 10 million people aged 50 and older in the United States, is characterized by low bone mass and weakened bones. It is known as a “silent disease” because it doesn’t cause symptoms. “People don’t usually find out until they experience a fracture, at which point the bone is already gone, Thus, identifying an individual at high risk is really needed to prevent these adverse events.” said Kyung Hyun Park-Min, PhD, scientist, Arthritis and Tissue Degeneration Program at HSS, and a lead author of the paper.

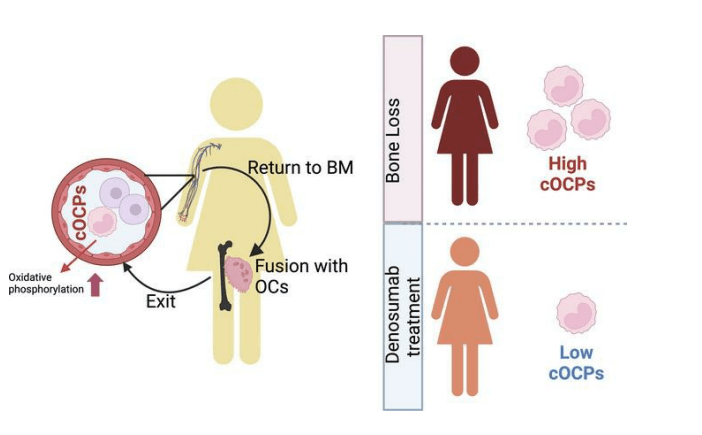

Bone is constantly being remodeled through a process of resorption, in which old bone tissue is removed by osteoclasts, and formation, in which the old bone tissue is replaced with new tissue created by cells called osteoblasts; bone begins to weaken when bone resorption exceeds bone formation. Circulating osteoclast precursor cells exacerbate bone resorption and loss by traveling through the bloodstream to the bones, where they fuse with resident osteoclasts.

In collaboration with HSS Endocrinology & Metabolic Bone Service, Drs. Park-Min and Bockman recruited 44 postmenopausal women, 16 of whom had untreated osteoporosis. Nine of the women had normal bone density and 19 had osteopenia (low bone mass). Blood tests were used to measure the quantity of cOCPs in the participants’ blood. The women with osteoporosis had significantly higher levels of cOCPs than those with normal bone density.

While the study sample was small and came from one center, the findings have implications for screening and treating osteoporosis.

Currently, bone density is measured by the DEXA scan, which is costly and typically only performed only every two years in older populations.

“The advantage of determining cOCPs is that it may identify individuals at high risk who may not yet have osteoporosis but have low bone density,” says Dr. Park-Min. “If we can identify these individuals before they suffer a fracture, we can recommend treatment options to promote healthy bones. Additionally, compared to current screening methods, detecting cOCPs through a simple blood test would be economically effective.”

The study also points to the significance of circulating cOCPs in joint replacement surgery outcomes.

“One potential complication of joint replacements is subsidence, or aseptic loosening,” Dr. Bockman said. “When this happens, it often necessitates surgical revision after arthroplasty.”

Dr. Park-Min’s team, in collaboration with the Complex Joint Reconstruction Center at HSS, is currently conducting research to determine the association between cOCPs and the incidence of aseptic loosening. “High osteoclast activity is one of the main factors contributing to aseptic loosening,” Dr. Park-Min said. “If we can detect changes in osteoclast activity after surgery, we can identify patients who are at risk for poor surgical outcomes. By identifying and targeting committed precursor cells, we may be able to improve surgery outcomes.”

Leave a Reply