Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) occurs when a blood clot forms in the brain’s venous sinuses. This prevents blood from draining out of the brain. As a result, blood cells may break and leak blood into the brain tissues, forming a hemorrhage.

This chain of events is part of a stroke that can occur in adults and children. It can occur even in newborns and babies in the womb. A stroke can damage the brain and central nervous system. A stroke is serious and requires immediate medical attention.

This condition may also be called cerebral sinovenous thrombosis.

What causes cerebral venous sinus thrombosis?

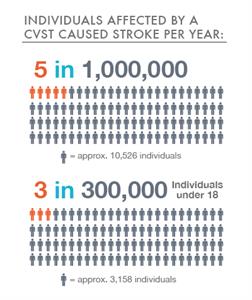

CVST is a rare form of stroke. It affects about 5 people in 1 million each year. The risk for this kind of stroke in newborns is greatest during the first month. Overall, about 3 out of 300,000 children and teens up to age 18 will have a stroke.

What are the risk factors for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis?

Children and adults have different risk factors for CVST.

Risk factors for children and infants include:

- Problems with the way their blood forms clots

- Sickle cell anemia

- Chronic hemolytic anemia

- Beta-thalassemia major

- Heart disease — either congenital (you’re born with it) or acquired (you develop it)

- Iron deficiency

- Certain infections

- Dehydration

- Head injury

- For newborns, a mother who had certain infections or a history of infertility

Risk factors for adults include:

- Pregnancy and the first few weeks after delivery

- Problems with blood clotting; for example, antiphospholipid syndrome, protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, lupus anticoagulant, or factor V Leiden mutation

- Cancer

- Collagen vascular diseases like lupus, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Behcet syndrome

- Obesity

- Low blood pressure in the brain (intracranial hypotension)

- Inflammatory bowel disease like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

What are the symptoms of cerebral venous thrombosis?

Symptoms of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis may vary, depending on the location of the thrombus. Responding quickly to these symptoms makes it more possible to recover.

These are the physical symptoms that may occur:

- Headache

- Blurred vision

- Fainting or loss of consciousness

- Loss of control over movement in part of the body

- Seizures

- Coma

How is cerebral venous sinus thrombosis diagnosed?

People who have had any type of stroke recover best if they get treatment immediately. If you suspect a stroke based on the symptoms, have someone take you immediately to the emergency room, or call 911 to get help.

Doctors typically take a medical history and do a physical exam. Family and friends can describe the symptoms they saw, especially if the person who had the stroke is unconscious. The final diagnosis, however, is usually made based on how the blood is flowing in the brain. Imaging tests show areas of blood flow. These tests may be used to diagnose venous sinus thrombosis:

- MRI scan

- CT scan

- Venography

- Angiography

- Ultrasound

- Blood tests

How is cerebral venous sinus thrombosis treated?

Treatment should begin immediately and must be done in a hospital. A treatment plan could include:

- Fluids

- Antibiotics, if an infection is present

- Antiseizure medicine to control seizures if they have occurred

- Monitoring and controlling the pressure inside the head

- Medicine called anticoagulants to stop the blood from clotting, after having excluded autoantibodies against platelets,

- Surgery

- Continued monitoring of brain activity

- Measuring visual acuity and monitoring change

- Rehabilitation

What are the complications of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis?

Complications of venous sinus thrombosis include:

- Impaired speech

- Difficulty moving parts of the body

- Problems with vision

- Headache

- Increased fluid pressure inside the skull

- Pressure on nerves

- Brain injury

- Developmental delay

- Death

POST VACCINE IMMUNE THROMBOTIC THROMBOPENIA

The blood clots reported in the six cases in USA are known as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST); in all cases, the clots were seen in combination with low levels of blood platelets, a condition known as thrombocytopenia. All occurred among women between the ages of 18 and 48, the statement from the CDC and FDA said, and symptoms occurred between six and 13 days after vaccination. In addition to the fatal case, one of the women is in critical condition.

As of Monday, more than 6.8 million doses of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine have been administered in this country. The vaccine is given as a single dose.

“You have a greater chance of being in a car accident on the way to getting this vaccine than you have of having a problem from this vaccine. But that’s not how people view risk,” said Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Philadelphia Children’s Hospital.

In Europe, where the AstraZeneca vaccine is being widely used, at least 222 suspected cases have been reported among 34 million people who have received the vaccine.

In The New England Journal of Medicine reported their findings on 16 of 222 cases: one team describes 11 patients in Germany and Austria and the other has observations on five patients in Norway. Both teams found the patients had unusual antibodies that trigger clotting reactions, which use up the body’s platelets and can block blood vessels, leading to potentially deadly strokes or embolisms.

The symptoms resemble a rare reaction to the drug heparin, called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), in which the immune system makes antibodies to a complex of heparin and a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4), triggering platelets to form dangerous clots throughout the body. Sickened vaccine recipients also had antibodies to PF4, the researchers found.

The researchers who studied the German and Austrian patients, led by clotting expert Andreas Greinacher of the University of Greifswald, had initially called the syndrome vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia; both teams now suggest a slightly simpler name: vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT).

In their paper, Greinacher and his colleagues also speculate about a possible mechanism. Vaxzevria consists of an adenovirus engineered to infect cells and prompt them to produce the virus’ spike protein. Among the 50 billion or so virus particles in each dose, some may break apart and release their DNA, Greinacher says. Like heparin, DNA is negatively charged, which would help bind it to PF4, which has a positive charge. The complex might then trigger the production of antibodies, especially when the immune system is already on high alert because of the vaccine. An immune reaction to extracellular DNA is part of an ancient immune defense triggered by severe infection or injury, Greinacher notes, and free DNA itself can signal the body to increase blood coagulation.

Alternatively, the antibodies may already be present in the patients and the vaccine may just boost them. Many healthy people harbor such antibodies against PF4, but they are kept in check by an immune mechanism called peripheral tolerance, says Gowthami Arepally, a hematologist at the Duke University School of Medicine who is working as an external consultant with AstraZeneca on the issue. “When you get vaccinated, sometimes the mechanisms of peripheral tolerance get disrupted,” she says. “When that happens, does that unleash any autoimmune syndromes that you are predisposed to, like HIT?”

Early suggestions that the rare reactions may be the result of a COVID-19 infection before vaccination have not been substantiated. None of the five patients in Norway had been infected, for instance. Others have suggested that antibodies against the virus’ spike protein—which many vaccines seek to elicit—somehow cross-react with PF4. That could spell trouble for nearly all COVID-19 vaccines. But so far, there is no evidence that the messenger RNA–based vaccines made by the Pfizer-BioNtech collaboration and Moderna, which tens of millions of people have received, are causing similar clotting disorders.

Pinpointing the mechanism is crucial to understanding whether other vaccines made from a modified adenovirus, which include those from Johnson & Johnson and CanSino Biologics, as well as Russia’s Sputnik V, do something similar.

The reported results in Europe are explaining only 16 cases, thus research needs to identify the others looking at iTTP, HUS, APS, ADAMTS13 and clotting factors congenital defect.

Leave a Reply